Andrew Loog Oldham Stoned Pdf Writer

Popular ebooks about Arts are available for free download on our resource - Legal Download. The Bert Berns Story and his interview with editor and co-director Bob Sarles is now exhibited on CaveHollywood.com. A Harvey Kubernik 2000 interview with onetime Rolling Stones' manager/record producer Andrew Loog Oldham quoted in Joseph's McComb's OUT magazine August 2017 article on Beatles' manager.

Rock and roll, a popular music craze of the mid-1950s, turned a loud, fast, and sexy set of sounds rooted in urban, black, working class, and southern America into the pop preference as well of suburban, white, young, and northern America. By the late 1960s, those fans and British counterparts made their own version, more politicized and experimental and just called rock—the summoning sound of the counterculture. Rock’s aura soon faded: it became as much entertainment staple as dissident form, with subcategories disparate as singer-songwriter, heavy metal, alternative, and “classic rock.” Where rock and roll was integrated and heterogeneous, rock was largely white and homogeneous, policing its borders.

Notoriously, rock fans detonated disco records in 1979. By the 1990s, rock and roll style was hip-hop, with its youth appeal and rebelliousness; post‒baby boomer bands gave rock some last vanguard status; and suburbanites found classic rock in New Country. This century’s notions of rock and roll have blended thoroughly, from genre “mash-ups” to superstar performers almost categories unto themselves and new sounds such as EDM beats. Still, crossover moments evoke rock and roll; assertions of authenticity evoke rock.

Because rock and roll, and rock, epitomize cultural ideals and group identities, their definitions have been constantly debated. Initial argument focused on challenging genteel, professional notions of musicianship and behavior. Later discourse took up cultural incorporation and social empowerment, with issues of gender and commercialism as prominent as race and artistry. Rock and roll promised one kind of revolution to the post-1945 United States; rock another. The resulting hope and confusion has never been fully sorted, with mixed consequences for American music and cultural history.

Every year, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum in Cleveland announces nominees for induction and the debate begins again. What is rock and roll? Is it the same thing as rock? Why does the nominating committee repeatedly propose the disco band Chic, only to see them rejected by an electorate more inclined to vote for, as in 2015, hard rockers Deep Purple? How can the hip-hop group N.W.A have been voted in if hip-hop is outside rock and roll altogether? Answers turn on how rock and roll has defined itself—or failed to.

Even the spelling is in question: many prefer rock ‘n’ roll to emphasize, positively or negatively, its unlettered qualities. A prominent disc jockey, arriving in New York City in 1954 after success in Cleveland, called his radio show Alan Freed’s Rock and Roll Party. The biggest hit since “White Christmas,” providing the opening soundtrack to Blackboard Jungle in 1955, was Bill Haley’s “(We’re Gonna) Rock Around the Clock.” And by 1956, there was a “king” of rock and roll: Elvis Presley, the biggest new pop star of the decade. Rock and roll’s identity was intensely mediated: a DJ’s slang, a movie tie-in, an overnight sensation. Skip ahead fifteen years, to about 1970 and the publication of The Sound of the City: The Rise of Rock and Roll, by Charlie Gillett, the first historian of the form but also a young amateur who wrote early drafts for fanzines.

Gillett’s generation claimed discursive control over the music they had grown up on. As simply rock, this era spawned its own FM radio, a hippie vision where rock and roll had relied on Top 40. There were rock festivals and arena concerts, headlined in full sets by white male acts like the Rolling Stones, where the more diverse 1950s groups played package tours of short sets.

And at rock magazines such as Rolling Stone, writers shared a background with musicians, replacing earlier press incredulity. Make one more jump to the mid-1980s, when artists were first inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and “classic rock” stations introduced. The best days of rock seemed behind it. The Rolling Stones became their own revivalists.

Rolling Stone promised advertisers yuppie readers. Punk rebellion had failed. Spandexed hair metal bands screamed fecklessness to all but their millions of devotees. MTV made new pop icons like Madonna, with synth-driven hits and arguably more visual than musical cleverness—was that rock at all? Rap was emerging: the new leaders, Run-D.M.C., called themselves “Kings of Rock.” There would be further chapters in the story but the pattern was set.

Rock and roll existed as an ideal—a note to hit, the invocation of an inclusive, pop-leaning American wildness. In its fragmentation, rock remained more identifiable, but compromised and in decline. Yet no forms of popular music, if you could put Humpty together again, were bigger in appeal or in influence on performers. Rock and Roll is Here to Stay: The 1950s It took almost a decade for rock and roll’s musical arrival to translate. The sound was fixed by 1947 Los Angeles, as Roy Brown, renaming the jump blues of Louis Jordan, wrote and performed “Good Rocking Tonight.” Brown’s small combo fused blues chords, jazz riffs, dance beats, and pop song structure into a party on wax that made the race records charts.

Wynonie Harris’s cover version topped those charts in 1948, as WDIA in Memphis became the first black-oriented radio station. In 1949, Billboard renamed race records rhythm and blues (R&B), the format that most birthed rock and roll. Elvis Presley, a teenage southern white and WDIA listener nonetheless, covered Harris’s cover for Memphis independent Sun Records in 1954. When he sang “let’s rock,” rock and roll became an identity beyond music. Most Americans didn’t register that, or Presley, until 1956. To bring that about, a few things happened in tandem as technology changed music, recording, and distribution.

Instruments electrified, particularly guitar, with sounds that had been background now in lead roles. Magnetic recording made it easier to edit studio work and highlight, even exaggerate, effects, from guitar solos to the taunting twitches in Presley’s vocals. Records increasingly came in two sizes, with 78 RPMs replaced by longer playing albums on 33 and the rock and roll and indie label choice, singles, on 45. Playing singles were radio stations that relied on disc jockeys spinning records, with network feeds increasingly lost to television.

These developments brought prominence to styles and audiences long considered marginal. The music of black and white southerners, divided into separate categories by record companies, overlapped stylistically. In the postwar era, R&B found a counterpart in the electrified country of honkytonk and western swing. “Rocket 88,” a 1951 R&B chart-topper on Sun by Jackie Brenston and his Delta Cats (including Ike Turner and a “fuzz guitar” solo caused by a busted amp), was covered in a similar fashion by Bill Haley and the Saddlemen for country fans, as Haley began the merger popularized with “Rock Around the Clock.” R&B and hillbilly boogie shared more than songs. Each amplified the lives of working class people with loose bills and loosened rules, moving north and to urban or suburban streets in a Great Migration for white as much as black southerners.

Each recorded for independents like Sun, proliferating in the postwar boom. If rock and roll rose on technological advances and the emboldened position of black and white working classes, its assimilation fed on changes in middle-class suburban America, where prosperity joined with Cold War fears in an era of domestic “containment”—younger marriages, a baby boom, and the nuclear family as resistance to communism. Suburban sterility is often summed up in rock history through the most dreaded pop hit of all: Patti Page’s 1953 “Doggie in the Window.” Singing primly—though the contemporary tracking let her harmonize with herself—about a puppy, heard yipping in rhythm, Page was all rock and rollers opposed. Listeners chose a different canine, Presley’s “Hound Dog,” whose roots and routes modeled rock and roll diversity.

Songwriters Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller were young Jews enthralled by black pop. The original R&B hit was produced by Johnny Otis, born Ioannis Alexandres Veliotesa to Greek immigrants, who “passed” in Los Angeles for black. Alabama-born singer Big Mama Thornton dressed as a man, presenting a transgressive sexuality. Houston record label, Peacock, was a black-owned independent. Presley’s later version built on a comic parody; Freddie Bell and the Bellboys did white takes on R&B in Las Vegas lounges. But the joke was at first on Presley, a former truck driver, when rock and roll hating New York TV host Steve Allen had him don black tie to sing “Hound Dog” to an actual basset. Furious, Presley recorded “Hound Dog” the next day, turning Thornton’s gender blur into class outrage: “you said you were high class, but that was just a lie.” The result topped pop, R&B, and country charts alike.

The gender, class, and regional contrasts between “Doggie in the Window” and “Hound Dog” were less discussed than race and propriety in the “leerics” and “big beat” preoccupations of 1950s pop commentary. But they mattered, just as it did that older star Frank Sinatra, an Italian American steeped in jazz, Broadway standards, and leftist Popular Front culture, hated both songs as infantile, responding with adult pop albums and a dissolute Rat Pack persona. Swinging cosmopolitanism blended immigrant and Harlem New York hustle, jazz band brass, movie and radio star intimacy.

But formations of American music moved away from this Tin Pan Alley and show business nexus. The rocking newcomers were younger, overtly southern and black in ways that registered as raw, less professional. To offer examples from the Rock Hall roster: Little Richard’s falsetto-tinged, piano-banged, former gay bar anthem, “Tutti Frutti,” defined rock and roll wildness, though Jerry Lee Lewis was a hillbilly (now “rockabilly”) rival. The shrewd lyrics and guitar licks of Chuck Berry’s “Maybellene” created the rock and roll singer-songwriter, as did Buddy Holly’s younger, whiter, and nerdier anthems.

Fats Domino gave a face to New Orleans rhythms, the roll in rock and roll. Ray Charles and Johnny Cash were genius synthesizers of Americana, Etta James the greatest female rocker of the period. The Drifters and Frankie Lymon’s Teenagers were early boy bands, doo wop fashioning rock and roll of nonsense syllables and romantic hyperbole.

Structurally, though, rock and roll was unsound. Its home was Top 40 radio, happy with hits of any kind: Pat Boone covering Little Richard, Fabian as teen pinup promoted on Dick Clark’s afternoon TV show American Bandstand. Artists had little control over mercurial careers: Presley was drafted, steered by his manager; Little Richard left pop for religion; Berry found himself imprisoned on racist sex charges; Lewis became ostracized for marrying a young second cousin; Holly died in a plane crash on a flimsy package tour. In an era of burgeoning civil rights, rock and roll embodied new racial freedoms more than it could articulate them explicitly. Many fans moved on as they hit college.

Perhaps, some thought, it had all just been a fad. You Say You Want a Revolution: Rock in the 1960s In 1964 the Beatles arrived in America, taking over Top 40 in a British Invasion.

Much had happened earlier in the decade: a folk craze, girl groups and Beach Boys, Motown Records, the Twist. But Beatlemania was a rock and roll revival. “Nothing really affected me until Elvis,” John Lennon said, and the Fab Four used an Ed Sullivan TV appearance to become iconic much as Presley had. “I Want to Hold Your Hand” was not the message: that transmitted when the music surged in pace and girls in Sullivan’s audience screamed and took over the camera. Unlike before, this 1960s incarnation of rock and roll matured.

Taking a critique of mass culture from the musical pilgrims assembled at the Newport Folk Festival, it became a rock counterculture gathered less earnestly at Monterey in 1967 and Woodstock in 1969. The Beatles no longer performed live; they made increasingly complex albums. Songs like “Strawberry Fields Forever,” with its Indian instruments and backwards tape effects, used the multitrack recording studio—and unlimited budget—to produce a blockbuster product with an artsy feel, alluding to psychedelic drug experience without much concealment.

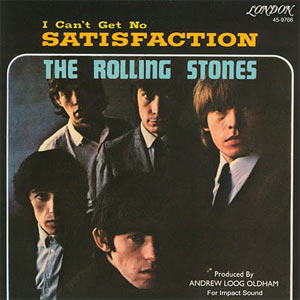

Formal experimentation, social experimentation, and big business carved rock from rock and roll. The Rolling Stones, named for a Muddy Waters song, formed in London of shared kinship for blues, pursuing non-pop lineages. “Satisfaction” in 1965 poked fun at advertising even as it conquered commercial-laden U.S. “Street Fighting Man” answered Motown’s “Dancing in the Streets,” accompanying protests at the 1968 Democratic convention. In 1969, the Stones topped the charts with “Honky Tonk Women,” which nodded to country and blues in its title and sound, then sex and drugs in a lyric allowed airplay: “she blew my nose and then she blew my mind.” That year, the group toured America, propagating a rock culture built around communal yet commercial gathering. The most consequential rocker of the decade barely played rock and roll. Fairpoint Spread 8 Keygen Download.

Bob Dylan, whose early “Song to Woody,” for folksinger Woody Guthrie, made the cross-generational claim the Stones did with Waters, was known for poetic anthems, both collective (“Blowin’ in the Wind”) and personal (“Mr. Tambourine Man”). But when the Beatles rekindled rock and roll he found “Tambourine Man” charting in a “folk-rock” version by the Byrds and readied his own electric reinvention, “Like a Rolling Stone.” A number 2 hit despite exceeding six minutes, the anthem’s influence was deregulatory: pop structures were optional, lyrics could be obscure, an unpolished voice had broad appeal. Dylan’s persona redefined the singer-songwriter to represent the most college-educated cohort in American history. Rock differed from rock and roll because it meant albums alongside singles, counterculture over youth culture.

By the 1967 triumphs of Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin at the Monterey Pop Festival, rare examples of alternatives to white men in lead roles, major record labels understood that rock’s sales and status dwarfed other music. Finishing what Sinatra and adult pop from Ray Charles to West Side Story started, rockers demanded creative freedom. Rock, a mainstream commercial form, positioned itself as anti-commercial or at least “authentic”: built around either the romantic authenticity of personal and communal experience or the modernist authenticity of newness and experiment. Whereas rock and roll’s popularity in the 1950s led to the music becoming softer, rock’s led to the music becoming louder: a response to violent times and the Vietnam draft, technology letting city-sized audiences hear every sustained note.

Rock and roll lacked structural support, but rock had foundations in radio, touring, media, and urban neighborhoods. FM radio became the home for rock channels that began as stoned sounding “underground” or “free form” stations. Woodstock and Altamont were poorly organized music festivals, but the crowds they drew demonstrated the commercial potential of more organized tours. And the underground press of the era was funded by record industry advertisements and other merchants participating in what became known as “Hip Capitalism.” Rolling Stone magazine, in particular, a countercultural newspaper when it began in the hippie Bay Area, empowered a new creature, the rock critic, to argue over the meaning of the music, past and present. San Francisco itself, a bohemian haven earlier for the Beat poetry scene in North Beach, the most important of the Pacifica public radio stations (KPFA), and the writing of culture critics such as music’s Ralph Gleason and film’s Pauline Kael, became the American city that most defined the new rock sensibility, as the Haight-Ashbury district hosted the summer of love in 1967 and brought the Jefferson Airplane, Grateful Dead, and Joplin to prominence.

Still, as the 1960s ended, rock’s revolutionary moment passed. Star deaths from drug use (Hendrix, Joplin, Jim Morrison) proved the risks of new mores. Divides separated younger audiences who sought hard rock and former folkies who favored singer-songwriter messages.

Undergrounds began to appear, with influential recordings like the Velvet Underground’s “Heroin” set at the fringe. Black fans and performers used rock notions to redefine R&B as soul and funk—they had to, shut out from rock’s definition as art even as James Brown’s rhythmic changes were the decade’s most revolutionary. This era dominates discussion of rock’s peak, yet it was really only a few short years—the length, say, of a college education. Arenas and Formats: Rock in the 1970s Cultural memory of rock in the 1970s has been framed through movies. Cameron Crowe looked back on his youth profiling bands for Rolling Stone in Almost Famous. Richard Linklater recalled his Texas high school in Dazed & Confused.

Both films show how widely rock values proliferated by the middle of the decade: high school as much as college, middle and working class, stoners and jocks, boys and girls, with the music supporting sex and drug uses that felt, somehow, innocent. Rock bands became akin to deities. Crowe recreates Led Zeppelin’s leonine lead singer, Robert Plant, announcing “I am a golden God!” in a wasted moment. Rock was now an industry, fit for arenas and stadiums everywhere.

Major label executives, notably David Geffen (who would become a billionaire in the process), made Southern California the geographic center for record labels and rock the core genre of pop. Rockers like Zeppelin and Grand Funk Railroad, criticized by critics and countercultural listeners as unprogressive, used the improved execution (stacked amplifiers, lighting to separate band from audience, reliable security) to showcase rock bigness as a triumph unto itself. “Cock rock,” as some called it, rooted in the working-class masculinity that connected electrified R&B and honkytonk country.

But this version, the swagger and long guitar solos of anthems like “Whole Lotta Love,” or ballads like “Stairway to Heaven” saluted with lit cigarette lighters, let a young, white, male-dominated counterculture cross class lines. Marketing it was the 18‒34 year-old male-focused format of rock radio, AOR (album-oriented rock), geared to play arena rock’s warhorses constantly, fetishistically.

Singer-songwriters emerged as no less commercially dominant, especially in album sales, creating a middle of the road soft rock known on radio by 1980 as “adult contemporary.” From Simon and Garfunkel’s Bridge over Troubled Water and Carole King’s Tapestry, the biggest albums ever to that point, to the mellow James Taylor and Jackson Browne or arena groups with akin sensibilities like Fleetwood Mac and the Eagles, singer-songwriters connected more to 1960s values than hard rockers. Their key subject, feminism and altered gender notions, used rock’s literacy and middle-class formal address to normalize social change as new bourgeois identity: contemporary casual, laid-back but still wealthy. The decade was a golden age for the artistic LP: Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, Bruce Springsteen, and David Bowie, among others, explored changing taste and behavior in ways both intensely personal and commercially public, with supportive major labels.

Those that critic Robert Christgau called “semipopular” performers, such as poet Leonard Cohen or sardonic balladeer Randy Newman, found stable perches too. Rock critics, who had emerged in underground publications at first, now held staff positions at daily newspapers and magazines; they reinforced the discourse that treated rock more as a new art form than an ephemeral commodity, with books from The Sound of the City to Greil Marcus’s soon hallowed Mystery Train and the critical collection, The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock and Roll, sealing in a narrative. In emphasizing artistic control, albums, splashy staging, and commercial anti-commercialism, rock shaped other categories. Soul and funk musicians recorded landmark albums and staged concerts akin to arena rock; some, like Aretha Franklin and Stevie Wonder, reached rock fans, but most, like Maze or the Ohio Players, did not.

Bob Marley, symbol of Third World Black Nationalism, was groomed to Dylan dimensions by label head Chris Blackwell. In country, outlaw figures like Willie Nelson, who rejected Nashville for more countercultural Austin, created a “redneck rock” hybrid; southern rockers Lynyrd Skynyrd and the Allman Brothers stressed regional pride. Salsa musicians, New Yorkers with roots from Puerto Rico to Panama, provocatively reinvented Latin music. Rock even affected newer classical: Einstein on the Beach resembled the Who’s rock opera Tommy. Ultimately, though, the corporate 1970s version of rock counterculture smashed up as the decade progressed, like the United States and United Kingdom overall.

Competing for the title of the biggest rock album of the decade was Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon, a stoned vision that new teens found endlessly fascinating, keeping it in Billboard’s charts for 741 weeks between 1973 and 1988. “Art rock,” or “progressive rock,” was rock quite distant from rock and roll. A revival movement, punk, started in New York around the nightclub CBGB, its most influential band the loud, fast, dumb acting Ramones, whose “Blitzkrieg Bop” compared arena shows to Nazi rallies. In London, an angry young man scrawled I Hate across his Pink Floyd shirt, took the name Johnny Rotten, and began British punk singing for the Sex Pistols. When Presley died in 1977, critic Lester Bangs eulogized not the King but rock and roll, now too fragmented to connect races, classes, regions, or tastes. If punk offered a backlash against mainstream rock, disco suffered a backlash led by mainstream rock. The dance craze, with its cross-racial appeal, Top 40 hits, and coded gay content (akin to Elton John in pop, Queen in arena rock, glam and Bowie as subculture), recalled earlier rock and roll.

But not rock, whose AOR fans, outraged when heroes like the Rolling Stones “went disco” or radio stations switched to disco formats, gleefully destroyed disco records at a 1979 rally led by a rock DJ. Disco survived, as club music, as MTV pop, even as new wave in conjunction with rock. Mainstream rock, though, a caricature in punk attacks and its own disco attacks, never recovered its progressive image. Commercially successful rock now seemed compromised.

The hallowed years of rock were behind it. Commodifying Dissent in the 1990s The blockbuster products of 1991 set the tone for the decade’s reuniting of rock with rock and roll. Metallica’s self-titled “black” album, the biggest of the bunch, joined metal and punk for working-class listeners who no longer believed in a utopic “Stairway to Heaven” or even hair metal glamor. Pearl Jam and Nirvana’s albums, major label versions of a Seattle grunge scene centered on the indie label Sub Pop, worked the same punk-metal fusion for middle-class listeners within the creative capitalism that nurtured Microsoft, Amazon, and Starbucks. And the industry marveled at the first Lollapalooza tour, which revealed a new rock and roll hybrid: alternative rock and hip-hop acts sharing the stage for a pierced and tattooed post-boomer audience, dubbed Generation X.

Grunge, gangsta rap, and New Country all claimed a large, engaged audience in the early 1990s, inheriting parts of rock’s mantle. Top 40 declined, crossover less necessary given these expanded segments. It was the return of counterculture, if with blatant sponsorship and major labels that struck deals with Sub Pop or hip-hop’s Death Row, incorporating indie and street marketing into global corporations: only one major was now American owned. Rock radio resumed playing new music. R&B incorporated hip-hop as figures like Dr.

Dre and Snoop Dogg hosted a groupie-filled party that resembled hair metal. Garth Brooks sold more albums, collectively, than anybody in the decade with an arena country that included Billy Joel and Aerosmith covers but no pop hits. Rolling Stone had magazine rivals in Spin (for alt-rock) and Vibe (for hip-hop and R&B). Once again, the revolutionary period proved short-lived. Notably, in the 1990s commercial popularity became an issue to an extent not seen before. In 1994, Nirvana leader Kurt Cobain, a heroin addict, killed himself in a tragedy viewed as reflecting his struggles with popularity; Pearl Jam stopped making videos and scaled back their ambitions.

The murders of rival West and East Coast rappers Tupac Shakur and Notorious B.I. Ge Smallworld Gis Software Download more. G. In 1995 and 1996 raised similar questions about the commodified rebellion of hip-hop. Brooks, like actual crossover country figures Shania Twain and Billy Ray Cyrus, found his popularity raising hackles among fans used to stars not getting above their raising.

A second key 1990s shift was that rock put women more front and center. If very male grunge claimed the spotlight, rock critiques launching from the riot grrrl scene just south in Olympia, Washington, were no less pivotal: Bikini Kill’s Kathleen Hanna gave Cobain the phrase “Smells Like Teen Spirit” and he saw his breakout as a blend of the two movements; in a different blend, Sleater-Kinney, another riot grrrl band, and grunge’s Pearl Jam became the region’s most lasting rockers, if at different levels of popularity. Commercially, Alanis Morissette’s Jagged Little Pill rivaled grunge and Metallica with an anthem, “You Oughta Know,” whose lyrics (“Is she perverted like me?/Would she go down on you in a theater?”) combined “Honky Tonk Women” and Madonna: a woman’s rock not pop. Songwriter Diane Warren dominated adult contemporary, while performer Sheryl Crow had “Hot AC” hits; this younger category aimed at women as rock listeners supported Hootie and the Blowfish, Gin Blossoms, and others.

New Country, from Twain to the Dixie Chicks, saw what one hit called “girls with guitars” chart higher than before or since. Lilith Fair offered a women’s music version of Lollapalooza. All of this made the contrast to hard rock and hip-hop masculinity striking. New arena rock, as the 1990s ended, was still dominated by a metal-punk fusion that now added hip-hop elements, recognizing the working-class commonalities. This could take a radical form: Rage Against the Machine played against the World Trade Organization protests of 1999.

Rock and roll recordings have never been easier to access, through streams from services like Spotify, individual tracks from YouTube, downloads via iTunes, and albums mail-ordered from Amazon. The harder challenge is to winnow down and find trustworthy discographical information: All Music Guide,, is invaluable as a first, not final reference point. YouTube has also made much more available rock and roll’s visual history: television appearances, music videos, concert footage.

The proliferation in the 2000s of DVDs made it almost as likely that a full-length visual recording would exist of a performer as an audio recording. Written material on rock and roll represents a second key growth area. For period critical writing, collects thousands of reviews and articles by leading British and American music press writers from the 1960s to 2000s. Databases preserve magazines and trade journal sources: notably, ProQuest’s Entertainment Industry Magazine Archive documents Billboard, Radio & Records, Melody Maker, New Music Express, and Spin.

Music memoir, a form adding stories to the record that were not told at the time, has flourished: examples include Chuck Berry, Ronnie Spector, Tommy James, Bob Dylan, Keith Richards, Pamela DesBarres’s groupie memoir, Loretta Lynn, Gregg Allman, Steven Tyler, Patti Smith, the oral history Please Kill Me, Viv Albertine, Nile Rodgers, Kristin Hersh, Jay-Z, Questlove, the RZA, and Carrie Brownstein. The rock documentary, or rockumentary, offers another way to survey rock and roll, so long as one watches as much to see how the story is being framed as to learn a direct lesson.

Among the most hallowed, including films that still document a pop moment: Good Rockin’ Tonight: The Legacy of Sun Records and Elvis: That’s the Way It Is (original rock and roll); The Beatles: The First U.S. Bennett, Andy, Barry Shank, and Jason Toynbee, eds. The Popular Music Studies Reader. New York: Routledge, 2006. Find this resource: • • Brackett, David, ed. The Pop, Rock, and Soul Reader: Histories and Debates. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Find this resource: • • Cateforis, Theo, ed. The Rock History Reader. New York: Routledge, 2013. Find this resource: • • Cepeda, Raquel, ed. And It Don’t Stop: The Best American Hip-Hop Journalism of the Past 25 Years. New York: Faber and Faber, 2004.

Find this resource: • • Echols, Alice. Hot Stuff: Disco and the Remaking of American Culture.

Norton, 2010. Find this resource: • • Forman, Murray, and Mark Anthony Neal, eds.

That’s the Joint: The Hip-Hop Studies Reader. New York: Routledge, 2012. Find this resource: • • Frith, Simon. Sound Effects: Youth, Leisure, and the Politics of Rock ‘n’ Roll. New York: Pantheon, 1981. Find this resource: • • Gillett, Charlie. The Sound of the City: The Rise of Rock and Roll.

New York: Pantheon, 1984. Originally published in 1970. Find this resource: • • Guralnick, Peter. Last Train to Memphis: The Rise of Elvis Presley. New York: Little, Brown, 1994. Find this resource: • • Hernandez, Deborah Pacini. Hybridity and Identity in Latino Popular Music.

Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2010. Find this resource: • • Keightley, Keir. “Reconsidering Rock.” In The Cambridge Companion to Pop and Rock. Edited by Simon Frith, Will Straw, and John Street, 109–142.

Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2001. Find this resource: • • Kramer, Michael J. The Republic of Rock: Music and Citizenship in the Sixties Counterculture. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Find this resource: • • Lipsitz, George. Time Passages: Collective Memory and American Popular Culture.

Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1990. Find this resource: • • Marcus, Greil.

Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock ‘n’ Roll Music. New York: Plume, 2015.

Originally published in 1975. Find this resource: • • Matos, Michaelangelo. The Underground Is Massive: How Electronic Dance Music Conquered America. New York: Dey Street Books, 2015. Find this resource: • • McDonnell, Evelyn, and Ann Powers, eds. Rock She Wrote: Women Write about Rock, Pop and Rap.

New York: Delta, 1995. Find this resource: • • Miller, Jim, ed.

The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll. New York: Rolling Stone Press/Random House, 1980. Find this resource: • • Moore, Ryan. Sells Like Teen Spirit: Music, Youth Culture, and Social Crisis. New York: New York University Press, 2009. Find this resource: • • Negus, Keith. Music Genres and Corporate Cultures.

New York: Routledge, 1994. Find this resource: • • Palmer, Robert. Rock & Roll: An Unruly History. New York: Harmony, 1995.

Find this resource: • • Savage, Jon. England’s Dreaming: Anarchy, Sex Pistols, Punk Rock and Beyond. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992. Find this resource: • • Waksman, Steve. This Ain’t the Summer of Love: Conflict and Crossover in Heavy Metal and Punk.

Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009. Find this resource: • • Wald, Elijah. How the Beatles Destroyed Rock ‘n’ Roll: An Alternative History of American Popular Music. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009. Find this resource: • • Walser, Robert. Running with the Devil: Power, Gender, and Madness in Heavy Metal Music. Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press, 1993.

Find this resource: • • Weisbard, Eric. Top 40 Democracy: The Rival Mainstreams of American Music. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014.

Find this resource: • • Willis, Ellen. Out of the Vinyl Deeps: Ellen Willis on Rock Music. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011. Find this resource: • • Zak, Albin.

I Don’t Sound Like Nobody: Remaking Music in 1950s America. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2010. Find this resource: • •.

() For guitar, see Robert Palmer, “Church of the Sonic Guitar,” in Present Tense: Rock & Roll and Culture, ed. Anthony DeCurtis (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1992) and Steve Waksman, Instruments of Desire: The Electric Guitar and the Shaping of Musical Experience (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999). For Presley’s vocalizing, see Edward Comentale, Sweet Air: Modernism, Regionalism, and American Popular Song (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2013). The best overview is Albin J.

Zak III, I Don’t Sound Like Nobody: Remaking Music in 1950s America (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2010). () Karl Hagstrom Miller, Segregating Sound: Inventing Folk and Pop Music in the Age of Jim Crow (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010); George Lipsitz, Rainbow at Midnight: Labor and Culture in the 1940s (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994); James Gregory, The Southern Diaspora: How The Great Migrations of Black and White Southerners Transformed America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005); John Broven, Record Makers and Breakers: Voices of the Independent Rock ‘n’ Roll Pioneers (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009). () Charles White, The Life and Times of Little Richard: The Quasar of Rock (New York: Harmony Books, 1985); W. Lhamon Jr., Deliberate Speed: The Origins of a Cultural Style in the American 1950s (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1990); Nick Tosches, Hellfire: The Jerry Lee Lewis Story (New York: Delta, 1982); Craig Morrison, Go Cat Go: Rockabilly Music and Its Makers (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1996); Robert Christgau, “Chuck Berry,” in The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll, rev. And expanded ed., ed. Jim Miller (New York: Rolling Stone Press/Random House, 1980), 54–60; Chuck Berry, The Autobiography (New York: Fireside, 1986); for Holly, Comentale, Sweet Air; John Broven, Rhythm and Blues in New Orleans, 3d ed.

(1988; reprint Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing, 2016); Robert Palmer, Rock & Roll: An Unruly History (New York: Harmony, 1995) and “Liner Notes for Ray Charles: The Birth of Soul in Blues & Chaos: The Music Writing of Robert Palmer, ed. Anthony DeCurtis (New York: Scribner, 2009), 163–188; Ray Charles and David Ritz, Brother Ray: Ray Charles’ Own Story (New York: Dial, 1978); Michael Streissguth, ed., Ring of Fire: The Johnny Cash Reader (New York: Da Capo, 2002); Alice Echols, “Smooth Sass and Raw Power: R&B’s Ruth Brown and Etta James,” in Trouble Girls: The Rolling Stone Book of Women in Rock, ed. Barbara O’Dair (New York: Random House, 1997); Etta James and David Ritz, Rage to Survive: The Etta James Story (New York: Villard, 1995); for doo wop, Brian Ward, Just My Soul Responding: Rhythm and Blues, Black Consciousness and Race Relations (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998). () Ellen Willis, “Dylan,” in Out of the Vinyl Deeps: Ellen Willis on Rock Music (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011); Bob Dylan, Chronicles, vol. 1 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004); Mike Marqusee, Wicked Messenger: Bob Dylan and the 1960s, rev.

(New York: Seven Stories Press, 2005); Lee Marshall, Bob Dylan: The Never Ending Star (Cambridge, U.K.: Polity Press, 2007); David Shumway, Rock Star: The Making of Musical Icons from Elvis to Springsteen (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014). () Greil Marcus, “Rock-a-Hula, Clarified,” Creem, June 1971, 36–52; Lester Bangs, “James Taylor Marked for Death,” Who Put the Bomp, Winter‒Spring 1971 and Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung, ed.

Greil Marcus (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1987), 53–81; David Browne, Fire and Rain: The Beatles, Simon & Garfunkel, James Taylor, CSNY, and the Lost Story of 1970 (New York: Da Capo, 2011); Clinton Heylin, From the Velvets to the Voidoids: The Birth of American Punk Rock, 2d ed. (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2005); RJ Smith, The One: The Life and Times of James Brown (New York: Gotham, 2012).

() Barney Hoskyns, Waiting for the Sun: Strange Days, Weird Scenes, and the Sound of Los Angeles (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996) and Hotel California: The True-Life Adventures of Crosby, Stills, Nash, Young, Mitchell, Taylor, Browne, Ronstadt, Geffen, the Eagles, and Their Many Friends (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2006); Sheila Weller, Girls Like Us: Carole King, Joni Mitchell, Carly Simon—And the Journey of a Generation (New York: Atria, 2008); Bruce J. Schulman, The Seventies: The Great Shift in American Culture, Society, and Politics (New York: Free Press, 2001). () Nelson George, The Death of Rhythm & Blues (New York: E. Dutton, 1988); Mark Anthony Neal, What the Music Said: Black Popular Music and Black Public Culture (New York: Routledge, 1999); Ward, Just My Soul Responding; Craig Werner, Higher Ground: Stevie Wonder, Aretha Franklin, Curtis Mayfield, and the Rise and Fall of American Soul (New York: Crown, 2004); Jason Toynbee, Bob Marley: Herald of a Postcolonial World? (Cambridge, U.K.: Polity Press, 2007); Jan Reid, The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock (1977; reprint Austin: University of Texas Press, 2004); Travis D.

Stimeling, Cosmic Cowboys and New Hicks: The Countercultural Sounds of Austin’s Progressive Country Music Scene (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011); Will Hermes, Love Goes to Buildings on Fire: Five Years in New York That Changed Music Forever (New York: Faber and Faber, 2011). () Simon Frith, Sound Effects: Youth, Leisure, and the Politics of Rock ‘n’ Roll (New York: Pantheon, 1981); Alice Echols, Shaky Ground: The Sixties and its Aftershocks (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002) and Hot Stuff: Disco and the Remaking of American Culture (New York: W. Norton, 2010); Tim Lawrence, Love Saves the Day: A History of American Dance Music Culture, 1970–1979 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003); Peter Shapiro, Turn the Beat Around: The Secret History of Disco (New York: Faber & Faber, 2005); Theo Cateforis, Are We Not New Wave? Modern Pop at the Turn of the 1980s (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2011). () David Toop, The Rap Attack: African Jive to New York Hip Hop (Boston: Serpent’s Tail, 1984); Tricia Rose, Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America (Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press, 1994); Raquel Cepeda, ed., And It Don’t Stop: The Best American Hip-Hop Journalism of the Past 25 Years (New York: Faber and Faber, 2004); Jeff Chang, Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2005); Dan Charnas, The Big Payback: The History of the Business of Hip-Hop (New York: New American Library, 2010); Murray Forman and Mark Anthony Neal, eds., That’s the Joint: The Hip-Hop Studies Reader, 2d ed.

(New York: Routledge, 2012). () Robert Duncan, The Noise: Notes from a Rock ‘n’ Roll Era (New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1984); Deena Weinstein, Heavy Metal: A Cultural Sociology (New York: Lexington Books, 1991); Chuck Eddy, Stairway to Hell: The 500 Best Heavy Metal Albums in the Universe (New York: Harmony, 1991); Donna Gaines, Teenage Wasteland: Suburbia’s Dead End Kids (New York: Pantheon Books, 1991); Walser, Running with the Devil; Klosterman, Fargo Rock City; Waksman, This Ain’t the Summer of Love; Weisbard, Top 40 Democracy.

() Lawrence Grossberg, Dancing in Spite of Myself: Essays on Popular Culture (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1997); George Lipsitz, Time Passages: Collective Memory and American Popular Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1990); Bernard Gendron, Between Montmartre and the Mudd Club: Popular Music and the Avant-Garde (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002); Gina Arnold, Route 666: On the Road to Nirvana (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1993); Michael Azerrad, Our Band Could Be Your Life: Scenes from the American Indie Underground 1981–1991 (New York: Little, Brown), 2001. () Alan Light, ed., The Vibe History of Hip-Hop (New York: Three Rivers Press, 1999); Eric Weisbard with Craig Marks, eds., Spin Alternative Record Guide (New York: Vintage, 1995); Will Hermes, ed., Spin: 20 Years of Alternative Music: Original Writing on Rock, Hip-hop, Techno, and Beyond (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2005); Bruce Feiler, Dreaming Out Loud: Garth Brooks, Wynonna Judd, Wade Hayes, and the Changing Face of Nashville (New York: Avon Books, 1998); David Hesmondhalgh, The Cultural Industries, 3d ed.

(London: SAGE, 2012); Timothy Dowd, “Concentration and Diversity Revisited: Production Logic and the U.S. Mainstream Recording Market, 1940‒1990,” Social Forces 82 (2004): 1411–1455. () Sara Marcus, Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution (New York: HarperPerennial, 2010); Carrie Brownstein, Hunger Makes Me a Modern Girl: A Memoir (New York: Riverhead Books, 2015); O’Dair, Trouble Girls; Evelyn McDonnell and Ann Powers, eds., Rock She Wrote: Women Write about Rock, Pop and Rap (New York: Delta, 1995); Sheila Whitely, ed., Sexing the Groove: Popular Music and Gender (New York: Routledge, 1997); Mary A. Bufwack and Robert K.

Oermann, Finding Her Voice: Women in Country Music, 1800–2000 (Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2003); Pamela Fox, Natural Acts: Gender, Race, and Rusticity in Country Music (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2009). () Simon Reynolds, Generation Ecstasy: Into the World of Techno and Rave (Boston: Little, Brown, 1998); Sarah Thornton, Club Cultures: Music, Media and Subcultural Capital (Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press, 1996); for reception of Radiohead’s shift away from rock, contrast Brent DiCrescenzo, 10.0/10 review of Kid A, Pitchfork, October 2, 2000, and Nick Hornby, “Beyond the Pale,” New Yorker, October 30, 2000; Grant Alden and Peter Blackstock, eds., The Best of No Depression: Writing about American Music (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2005); Richard A. Peterson and Bruce A. Beal, “Alternative Country: Origins, Music, World-view, Fans, and Taste in Genre Formation,” Popular Music and Society 25.1–2 (2001): 233–249; Barbara Ching, “Going Back to the Old Mainstream: No Depression, Robbie Fulks, and Alt.Country’s Muddied Waters,” in A Boy Named Sue: Gender and Country Music, ed.

McCusker and Diane Pecknold (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2004), 178–195; Degen Pener, The Swing Book (New York: Hachette, 1999); Bill Milkowski, Swing It: An Annotated History of Jive (New York: Billboard Books, 2001); Mark Anthony Neal, Soul Babies: Black Popular Culture and the Post-Soul Aesthetic (New York: Routledge, 2002). () For compendia of writing on rock and pop, including early accounts, see David Brackett, ed., The Pop, Rock, and Soul Reader: Histories and Debates, 3d ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013); Cateforis, The Rock History Reader; Hanif Kureishi and Jon Savage, eds., The Faber Book of Pop (London: Faber and Faber, 1995); Arnold Shaw, The Rockin’ 50s: The Decade That Transformed the Pop Music Scene (New York: Hawthorn Books, 1974); Charles Hamm, Putting Popular Music in Its Place (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995); Ennis, The Seventh Stream; Peterson, “Why 1955?”. () Willis, Out of the Vinyl Deeps; Christgau, Christgau’s Record Guide: Rock Albums of the ‘70s; Bangs, Psychotic Reactions; DeCurtis, Blues & Chaos: The Music Writing of Robert Palmer; Dave Marsh, The Heart of Rock & Soul: The 1001 Greatest Singles Ever Made (New York: Plume, 1989); Booth, The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones; Richard Meltzer, The Aesthetics of Rock (1970; reprint New York: Da Capo, 1987). For collections, focused on earlier writers, see William McKeen, ed., Rock and Roll Is Here to Stay: An Anthology (New York: W. Norton, 2000); Clinton Heylin, ed., The Penguin Book of Rock & Roll Writing (New York: Penguin, 1992). For histories, Powers, Writing the Record; Gendron, Between Montmartre and the Mudd Club; DeRogatis, Let it Blurt: The Life and Times of Lester Bangs, America’s Greatest Rock Critic (New York: Broadway Books, 2000); Robert Christgau, Going into the City: Portrait of a Critic as a Young Man (New York: Dey Street Books, 2015).

() Simon Frith, Taking Popular Music Seriously: Selected Essays (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2007); Lott, Love and Theft; Grossberg, Dancing in Spite of Myself; Hebdige, Subculture; Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993); Iain Chambers, Urban Rhythms: Pop Music and Popular Culture (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1985); Angela McRobbie, Postmodernism and Popular Culture (New York: Routledge, 1994); Thornton, Club Cultures; Negus, Music Genres and Corporate Cultures; Keightley, “Reconsidering Rock.”. () Rose, Black Noise; Neal, What the Music Said; Guthrie P. Ramsey Jr., Race Music: Black Cultures from Bebop to Hip-Hop (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003); Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003); Perry, Prophets of the Hood; Bakari Kitwana, The Rap on Gangsta Rap (Chicago: Third World Press, 1994); Lipsitz, Time Passages; Josh Kun, Audiotopia: Music, Race, and America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005). () McClary, Feminine Endings; Walser, Running with the Devil; David Brackett, Interpreting Popular Music (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000); Charles Keil and Steven Feld, Music Grooves: Essays and Dialogues (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994); Joseph G. Schloss, Making Beats: The Art of Sample-Based Hip-Hop (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2004); Cavicchi, Tramps Like Us; Susan D.

Crafts et al., My Music (Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press, 1993); John Covach and Graeme M. Boone, Understanding Rock: Essays in Musical Analysis (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997); Allan Moore, Rock, the Primary Text: Developing a Musicology of Rock (Brookfield, VT: Ashgate, 2001); Fast, Houses of the Holy; Albin Zak, The Poetics of Rock: Cutting Tracks, Making Records (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001); Theodore Gracyk, Rhythm and Noise: An Aesthetics of Rock (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1997). () Sanneh, “The Rap Against Rockism”; Douglas Wolk, “Thinking about Rockism,” Seattle Weekly, May 4, 2005; Jody Rosen, “The Perils of Poptimism,” Slate, May 9, 2006; Daphne A. Brooks, “The Write to Rock: Racial Mythologies, Feminist Theory, and the Pleasures of Rock Music Criticism,” Women and Music: A Journal of Gender and Culture 12 (2008): 54–62; Miles Park Grier, “Said the Hooker to the Thief: ‘Some Way Out’ of Rockism,” Journal of Popular Music Studies 25.1 (March 2013): 31–55; Carl Wilson, Let’s Talk about Love: A Journey to the End of Taste (New York: Continuum, 2007); Wald, How the Beatles Destroyed Rock ‘n’ Roll. See also essays first presented at the EMP Pop Conference, collected in Eric Weisbard, ed., This Is Pop: In Search of the Elusive at Experience Music Project (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004); Listen Again: A Momentary History of Pop Music (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007); and Pop When the World Falls Apart: Music in the Shadow of Doubt (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012). () Good Rockin’ Tonight: The Legacy of Sun Records (Chatsworth, CA: Image Entertainment, 2002), DVD; Elvis: That’s the Way It Is (1970; Burbank, CA: Warner Home Video, 2007), DVD; The Beatles: The First U.S.

Visit (1964; Hollywood, CA: Capitol Records, 2003), DVD; TAMI Show (1964; Los Angeles: Shout Factory, 2010), DVD; Don’t Look Back (1967; New York: Docurama, 1999), DVD; Monterey Pop (1968; Santa Monica, CA: Criterion, 2006), DVD; Woodstock (1969; Burbank, CA: Warner Bros.